Measuring environmental floods on the Spoel river: first field campaign

Campaign description

The Spoel is found in the Swiss National park and is a tributary of the Inn river. There is a hydropower plant (Kraftwerk Ova Spin) located upstream on the Spoel, and this hydropower plant consistently releases 0.9 m3/s except on the day of the flood where it releases enough water to reach 25.9 m3/s. The water is released in steady increments from 7:00-12:00 until it reaches 25.9 m3/s at noon, then the discharge decreases again until it is at its minimum (0.9 m3/s) at 16:00.

The night before the campaign

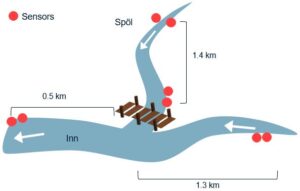

We arrived the day before the campaign to find some good locations to install the sensors. The locations where the sensors were installed is in Figure 1. The plan was to install two sensors upstream on the Spoel, two downsteam (just before the Spoel enters the Inn), two upstream on the Inn, and two downstream on the Inn just after the confluence. We wanted to install two sensors at each location to a) make sure the sensors were both outputting the same data and to b) ensure we got data even if one of the sensors stopped working for some reason.

Once we picked the locations, we installed some rebar in the river, very close to the banks. We would hammer the rebar into the river bed and then tie the top end of the rebar against a tree (usually we would pick locations where the tree is hanging over the river).

With this work completed, we only had to install the sensors in the morning before the flood was released. The reason we had to install the sensors immediately before the flood (and not the night before) is because we weren’t sure how long the sensors would last. When I tested the sensors previously, they would last anywhere from 5-10h depending on the measurement frequency. (I am not an electrical engineer, so when designing the sensors, I was mainly concerned with designing a good optical sensor. I wasn’t paying much attention to the voltage circuit and battery life.)

Flood day!

The day of the flood, we only had to install fresh batteries into the sensors and install the sensors with hose clamps against the rebar in the river before 7am (or risk getting caught in the flood). After this, the day was quite relaxing. A colleague of mine sat on the downstream end of the Spoel and took a water+sediment sample every 30min whereas I did the same thing but on the upstream end of the Inn (see Figure 1).

After the e-flood

When the flood was over and it was time to take the sensors out of the water, we found that one of the sensors at the upstream Inn location was completely covered in sediment (see Figure 1). So I’m pretty happy that I installed two sensors at this location, but one on each side of the river.

In June 2022, we didn’t have enough snowmelt to repeat the e-flood. We are hoping for enough water in June 2023 (where we will test our latest sensor prototypes). At the moment, the data from this June 2021 campaign is unpublished but the preliminary results were presented at EGU 2023 in April. And as a last point, the sensors used in this campaign were the first prototypes that were also tested in the mixing tank experiments:)